Swift’s chord progressions, melodies, structures, harmony, rhythm, and production are rooted in pop conventions.

The songstress’ songwriting success largely stems from her use of familiar chord progressions like I-V-vi-IV, which provide emotional resonance while allowing room for lyrical storytelling.

Swift’s melodies are simple yet effective, often featuring stepwise motion or conjunct motion, which is when a melody moves from one note to the very next note in a scale, creating a smooth and easy-to-sing line using adjacent notes. Swift also uses emotional arcs that mirror narrative builds in her lyrics.

Her dynamic song structures, featuring strong sectional contrasts and strategic bridges, contribute to the catchiness and replay value of her tracks.

Swift’s Chord Progressions

Swift regularly employs timeless progressions such as I-V-vi-IV (e.g., C-G-Am-F in C major), which create a sense of yearning and resolution.

This is evident in songs like “Love Story” and “All Too Well,” where the loop supports romantic themes. Other favorites include vi-IV-I-V for a minor-key start, adding melancholy, as in “Teardrops on My Guitar.”

In Love Story, Swift employs the same chorus melody throughout. The lyrics, however, change, improving the song’s narrative.

“It’s not common at all and is one of the main areas where Swift really goes against the grain,” said David Penn, who co-founded Hit Songs Deconstructed. “Just over half of her hits from Fearless through Midnights feature choruses with differentiated lyrics. However, most balance the new lyrics with recycled material from previous choruses to maintain a degree of familiarity and ensure that the song’s main ‘hook center’ gets firmly ingrained in the listener’s head.”

Swift is also unique in her pre-chorus delivery. Usually in pop music, writers use the same lyrics across a song. Three-quarters of Swift’s songs use different pre-chorus lyrics from one pre-chorus to the next.

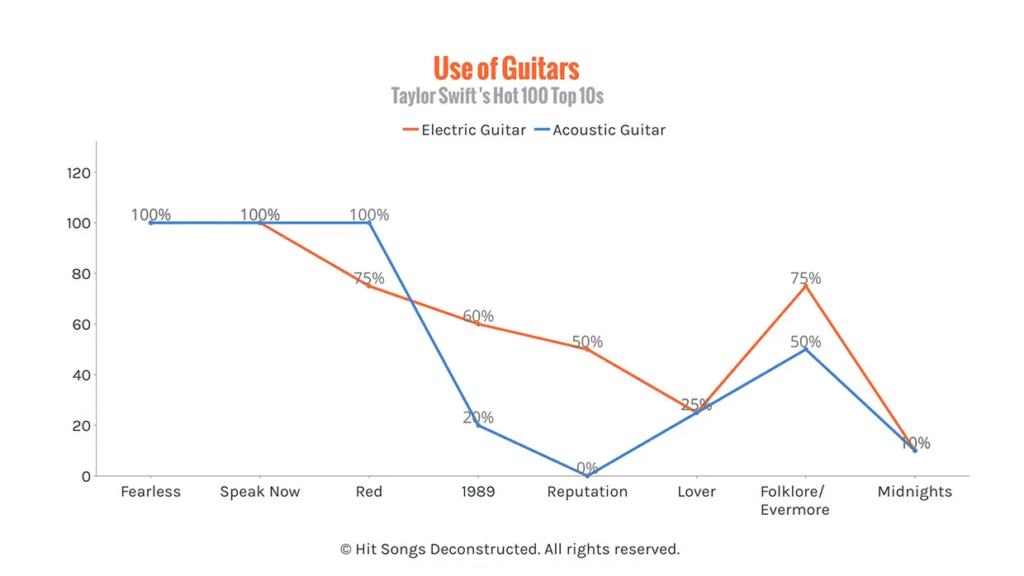

While electric and acoustic guitars were a fixture in Swift’s early sound, their uses began to decline after the album Red, except for singles from the albums Folklore and Evermore, which employed more towards singer-songwriter and folk styles.

Melodic and Harmonic Techniques

Her melodies often prioritize conversational contours with occasional leaps for emphasis, building emotional depth. For instance, in “Blank Space,” the verse melody outlines an F major triad with a pedal point for suspense. Harmonically, she layers thirds or fifths in choruses and uses subtle dissonances for tension, resolving them for impact.

Song Structures and Production

Swift’s structures typically follow verse-pre-chorus-chorus-bridge patterns, with periodic contrasts to maintain engagement. Production involves vocal layering and instrumental hooks, blending genres like country-pop or synth-R&B. This evolution is seen from Fearless to Midnights, adapting to trends while maintaining her core identity.

Compositional Techniques

Swift’s songwriting journey began in country music with albums like Fearless (2008), featuring straightforward narratives and simple harmonies to emphasize personal stories.

Early works employed diatonic progressions, which are chord progressions that use only chords built from the notes of a specific musical key’s scale, in major keys. This is in line with country music’s emphasis on relatability.

As Swift transitioned to pop with her 2014 album 1989, her techniques grew more sophisticated, incorporating modal interchange (borrowing chords from parallel keys, a major and minor key that share the same tonic, or starting note) and chromaticism, which is the use of notes outside the standard diatonic scale (the major or minor scale) of a composition to add “color” and complexity to the music.

Swift’s collaborations with producers like Max Martin introduced layered arrangements, as seen in her pseudonymous co-write “This Is What You Came For” (2016), which balances radio-friendly hooks with lyrical subtlety.

By Folklore and Evermore, both released in 2020, Swift embraced indie-folk elements, stripping down production for intimacy while maintaining melodic coherence.

2024’s The Tortured Poets Department, shows a return to synth-driven sounds but with experimental timbres, though some critics note a uniformity in keys and progressions.

Chord Progressions: The Foundation of Emotional Resonance

Swift’s music often depends on familiar chord loops.These progressions are masterfully deployed for emotional effect, as they evoke nostalgia and resolution.

The I-V-vi-IV (e.g., C-G-Am-F) is her most used, appearing in over 21 songs, including “Love Story,” “All Too Well,” and “Champagne Problems.”

The I-V-vi-IV progression uses four-chords: the tonic (I), dominant (V), submediant (vi), and subdominant (IV) chords of a major scale. It is known as the “Axis progression,” which creates a yearning loop that resolves on the tonic (I), builds tension with the dominant (V), and shifts to the melancholy of the relative minor (vi), before easing with the subdominant. (IV)

The vi-IV-I-V (e.g., Am-F-C-G): Starts minor for introspection, as in “Teardrops on My Guitar” and “Sparks Fly.”

This is a popular and emotionally resonant sequence with a melancholic feel. Let’s break this chord progression down:

VI (the Submediant): This is the sixth chord in the scale, and is a minor chord.

IV (the Subdominant): The fourth chord in the scale, a major chord.

I: The first chord in the scale, the root and home chord, meaning it is a major chord.

V (Dominant): The fifth chord in the scale, creating tension and a strong pull back to the I chord.

This progression holds a melancholic sound, a sad and longing feeling, while still containing major chords. This is caused by the VI (minor) chord, which sets the more somber tone.

This progression is used regularly in popular music, such as in songs like “Girls Like You” by Maroon 5 and “Zombie” by The Cranberries.

One variation of this progression, and one that is more common, is the I-V-VI-IV progression, which uses the same four chords in a different order, and is sometimes called the “Axis of Awesome” progression.

The VI-IV-I-V progression is sometimes considered the “pessimistic inversion” of this sequence.

The harmonic function of this progression provides a strong sense of resolution from the dominant (V) chord back to the tonic (I) chord, for a satisfying conclusion.

I-V-ii-IV (e.g., Bb-F-Gm-Eb): Builds a climbing feel, used in “Wildest Dreams” and “Getaway Car.”

The I-V-ii-IV chord progression is a common sequence in major keys, containing the major tonic (I), dominant (V), and subdominant (IV) chords alongside the minor supertonic (ii).

In the key of C major, it translates to C-G-Dm-F.

It often appears in pop, rock, and indie music as a variant of the more widespread I-V-vi-IV progression, providing a similar looping feel but with a potentially more introspective or driving quality due to the ii chord’s substitution for vi.

How It Functions

The progression creates harmonic tension and release: I establishes the key, V builds dominant tension, ii acts as a pre-dominant (sharing notes with IV for smooth transition), and IV provides subdominant resolution before looping back to I. This cycle often feels uplifting yet grounded, though some find the ii-IV transition less dynamic than alternatives like vi-IV.

I-vi-IV-V: The “50s progression,” evoking doo-wop melancholy in “Blank Space” and “White Horse.”

The “I vi iv V” chord progression is common and versatile, using the first, sixth, fourth, and fifth chords of a major scale.

In the key of C, this progression is C-Am-F-G. It is commonly used in rock, pop, and can be rearranged into the V-vi-IV-I progression, also known as the Axis progression, and can be heard in songs like “Let It Be” and “Don’t Stop Believing.”

In TTPD, most tracks stick to I, IV, V, and vi chords, with 14 in C major, contributing to a cohesive but potentially monotonous album sound. However, variations like IV-I-V-iii in “My Boy Only Breaks His Favorite Toys” add distinction.

Melodies: Simplicity Meets Narrative Depth

Swift’s melodies are designed for singability, using stepwise motion with leaps for dramatic emphasis.

They often follow emotional arcs: low and intimate in verses, rising in choruses to mirror lyrical climaxes.

In “You Belong with Me,” the melody ascends stepwise before leaping on “me,” creating relatability. “Blank Space” uses an F major triad outline in the verse with a pedal point (static note) for suspense, descending scalewise in the bridge for irony.

Harmonically, she layers parallel thirds or fifths for fullness, introducing dissonances like suspensions for tension-release. Subtle key changes, like the whole-step modulation in “All Too Well (10 Minute Version),” amplify drama.

Coined the term “Swiftism” to refer to “uniquely identifiable, embellishing vocal moment in a Swift hit.”

He explains that “they range from a laugh and a quip to clever and impactful song title hooks, which are often spotlighted by a moment of instrumental silence.”

According to, the first “Swiftism” appearing in a Hot 100 top hit is 2010’s “Speak Now,” and is really noticeable on 2012’s “We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together,” which features three of Swiftisms: the spoken “what” at the first stanza of verse 1. As well, the “like, ever” turnaround and bridge, as well as the laugh at the end of verse 2.

Swift hits also include audience participation moments (A.P.M.s).

“These are characteristics or moments in a song that are primed to get the audience singing, humming, clapping and/or stomping along with the performing artist in concert.”

Swift’s shouted lines in “Cruel Summer” at the end of each bridge stanza lend themselves perfectly to an A.P.M., in this song Swift’s emotions towards a love interest.

Song Structures: Building Tension and Release

Swift adheres to pop forms (verse-chorus-bridge) but varies with pre-choruses and post-choruses for momentum. Sectional contrast is key here: hushed verses against explosive choruses, as in “Love Story” or “Anti-Hero.” Bridges often introduce rhythmic shifts, like triplets in “Willow,” for contrast. In “Blank Space,” the bridge drops harmony entirely, focusing on vocals for stark irony.

Rhythm and Production: Driving Engagement

Rhythms are precise in 4/4 time with syncopation for energy, as in “Anti-Hero’s” kick-snare pattern. Production layers instruments dynamically: minimalist verses building to lush choruses with synths and strings. Vocal techniques include double-tracking and harmonies, evolving from country doubles to pop panning. Genre fusion broadens Swift’s appeal, like country-pop in “Fifteen” or indie-dream-pop in “Cardigan.”

In TTPD, production by Antonoff and Dessner uses thematic synths (e.g., shimmering in “Down Bad”), but mid-range vocals and similar tempos may blend tracks.

Critical Reception and “Secrets” to Success

While some debate repetition in Swift’s music, such as in the case of TTPD’s C-major dominance, it underscores her formula’s effectiveness. Ultimately, these techniques—rooted in theory yet adaptable—explain her enduring chart dominance.

Swift has minimized over the years the use of what Hit Songs Deconstructed call the section impact accentuator (SIA), in which parts or all the instrumentation are pulled from mix to spotlight a hook, often at the end of a chorus. A staple in early sounds, it became less frequent over time. It can be heard in her songs “Love Story,” “Ready for It?” and “Lover.”

Then there are some techniques that were once part of her signature sound but have since been dropped, possibly to avoid becoming too predictable or due to stylistic irrelevancy. A prime example is what we at Hit Songs Deconstructed call the S.I.A. technique: section impact accentuator. This is where parts or all the instrumentation are pulled from the mix to spotlight a hook, often at the end of a chorus. While this is a staple of Swift’s early sound, it became less frequent as time went on. You can really hear it in “Love Story,” “…Ready for It?” and “Lover,” among other songs.

A few other areas where she evolved with the times is her shift away from big, high-energy choruses; trimmed down song lengths; and lesser use of pre-choruses.

Leave a Reply